Minister who called for peace and lawfulness delivered 1963 commencement benediction

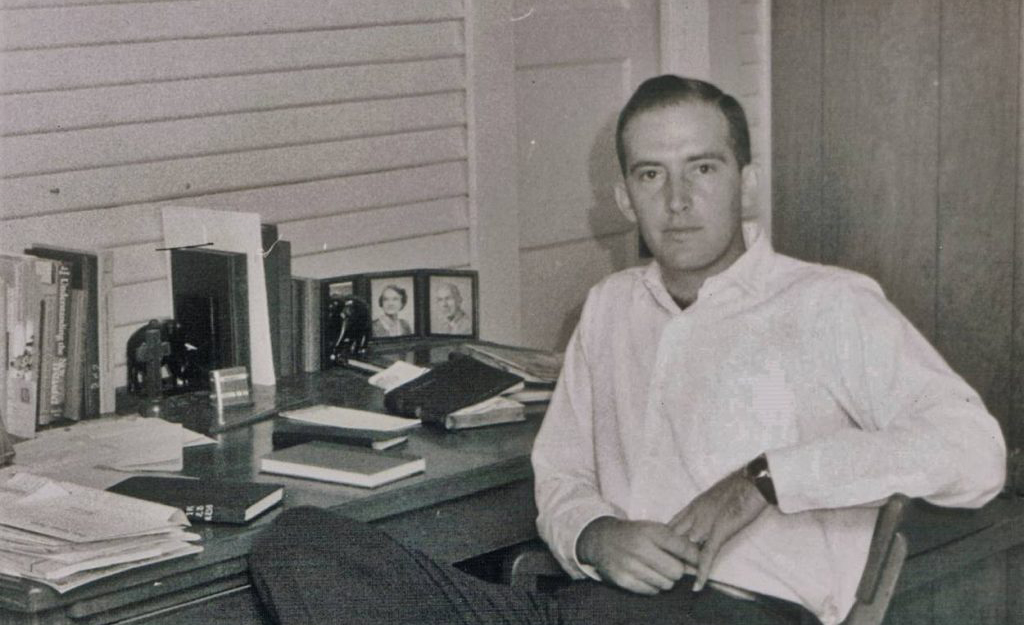

Presbyterian minister Cliff McKay reads in his study at the family home in Oxford in 1959. McKay was at the University of Mississippi as a chaplain from 1959 to 1964, and returned decades later to finish his master’s degree in philosophy in 2020. Submitted photo

MAY 10, 2023 BY STAFF REPORT

When James Meredith received his bachelor’s degree at the University of Mississippi‘s 1963 Commencement ceremony – less than one year following the university’s turbulent integration – he became not only its first African American student but also its first African American graduate.

Among those participating in the ceremony was Presbyterian minister Clifford A. McKay Jr. McKay served as the Presbyterian chaplain at the university from 1959 to 1964 and delivered the 1963 ceremony’s invocation and benediction.

During his time at UM, McKay counseled students and formed new interfaith groups. He also advocated for Meredith’s enrollment, joining with six local ministers and other denominational chaplains who wrote a telegram condemning the “defiance of federal court orders,” emphasizing the need for peacemakers and urging decision makers to “uphold the good name and dignity of the university.”

A resident of Winter Park, Florida, and retired from decades of ministering, McKay’s alma maters include Vanderbilt, Emory, the Union Theological Seminary, University of Ceylon and UM, where at 87, McKay completed a master’s degree in philosophy. This accomplishment makes him the university’s oldest graduate, according to electronic records beginning in 2004.

You came to the University of Mississippi in 1959. What were some of your previous experiences with integration, and what did you experience at the university?

I attended Union Seminary in Richmond, Virginia, which was integrated the first year I was there. One day, we were on assignment and missed lunch at the dining hall at the seminary and headed to a local restaurant to have lunch. We got to the door before we realized that our friend, Calvin, could not go in with us.

We asked him, “Calvin, when did you realize we had a problem?” He says, “Oh, come on, give me a break, guys. The moment I saw that the cafeteria at the refractory was closed, I knew we were in trouble.”

So this was the kind of experience that I had been in when I went to Mississippi. I also had gotten to know other Christian students from all over the country, and that broadened my Southern perspective.

I’d been at the university a year or two years when integration first came up. Segregationists throughout the state were very adamant about Meredith not entering the university. The ministers of Oxford felt like we had to address the issue.

Cliff McKay (second from right) visits with classmates at a Department of Philosophy and Religion tailgate in the Grove in fall 2019. McKay, who was a chaplain at the university from 1959 to 1964, says he is pleased how it has grown and diversified in the years since its integration. Submitted photo

We met weekly as the tension was building, over a cup of coffee, talking about things and what was going on and different approaches. We put out a joint letter that was read in Oxford churches and widely distributed throughout the state. There was a good bit of reaction to it. We were speaking out in terms of sanity and obeying the law, because Meredith was lawfully eligible to be a student there.

What was the atmosphere on campus and in Oxford in the months following the integration?

Things were very unsettled on campus. Attitudes and emotions were so raw at that point that sitting down, nobody could really talk or think about any other issues. There was a core group of students, a few of them from the Westminster Fellowship, who made it a point to sit by James Meredith in class and to walk with him across the campus. But there were other students who were strongly opposed to Meredith’s presence.

One day, a history professor, Jim Silver, said to me, “Cliff, you wanna play golf with me and Meredith on Wednesday afternoon?” This was sometime in February of that academic year. I thought a minute, and I said, “Sure.” So we met on the golf course. And as we played, we could see the 101st Airborne Division in the woods on either side. A truck backfired and we ducked down, thinking it was a rifle shot of some sort. We were that much on edge.

Throughout the year, there would be jeeps and soldiers parked at strategic places around campus. Meredith was surrounded and escorted wherever he went early on. Over time, they were removed. Dr. Silver asked Meredith,: “Do you notice these jeeps being there?” And Meredith said, “I don’t notice them being there. But if one of them is missing, I notice that immediately,” underlining the continuing threat and anxiousness even as things settled.

Looking back at that era, do any particular memories stand out?

Following the integration, the Westminster Fellowship and the political science department took a combined trip to Washington, D.C., to have an opportunity to meet with government leaders. We met with Sen. (John) Stennis, Sen. (Barry) Goldwater, Vice President (Lyndon) Johnson and with Nicholas Katzenbach, the assistant attorney general.

The students got to have interviews with them, and we did it twice. Katzenbach, who was assistant attorney general under Bobby Kennedy, had been in Mississippi supporting Meredith’s entry.

We made the trips with Ed Hobbs, who was the head of the political science department. We met with Bill Moyers, who was the head of the Peace Corps. Moyers attended the meeting because he had learned that the students were very interested, and he was pleased. Within a week, there were representatives from the Peace Corps recruiting at the University of Mississippi.

What was the atmosphere at James Meredith’s graduation ceremony?

There was a sense that the chancellor was eager to move forward and toward a new sense of normalcy. When James Meredith was awarded his degree, he was treated like all the other students. It was so different from when he enrolled. He had changed things.

You completed your master’s in philosophy at the university in 2020. Tell me your impressions of the university over the past 60 years.

I was amazed by how large and busy it was. There were few markers from 60 years ago. I was glad to see the mix of students that were there. It had grown and it was more diverse, much more diverse. It was significantly different from what it was when I was there 60 years before.

As Ole Miss celebrated the anniversary of Meredith’s graduation, I was pleased to see how the environment had changed. I did not expect this kind of difference in such a short period of time. I am happy to see the efforts the university has made to honor James Meredith. He was a very brave man.