Project uncovers wall plaster etchings buried by Mount Vesuvius

APRIL 25, 2018 BY

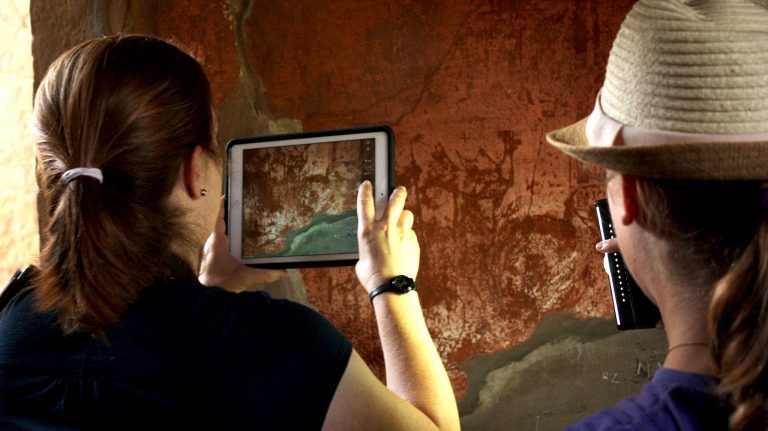

Rebecca Benefiel, an associate professor of classics at Washington and Lee University and Ancient Graffiti Project director, uses an iPad to photograph graffiti in Herculaneum, Italy. Submitted photo

Centuries before Kilroy was here, “Hyacinthus was here,” lurking around the streets of ancient Herculaneum, carving his eternal presence into wall plaster with graffiti.

Hyacinthus’ reminder is joined by other graffiti etched into the walls of the Italian town that was entombed under tons of volcanic pyroclastic flows from the erupting Mount Vesuvius in A.D. 79.

Other graffiti writers professed their love while some wrote short poetry or drew elaborate images of camels and women. And some, not surprisingly, carved obscenities or used their engravings to spread vicious rumors.

These inscriptions have been preserved for centuries by the weight of the exploding Vesuvius. Those graffiti and graffiti from the neighboring town of Pompeii, also buried by the blast of Vesuvius, are being documented and digitized by The Ancient Graffiti Project, a venture whose field director is University of Mississippi classics professor Jacqueline DiBiasie-Sammons.

“The Ancient Graffiti Project is an archeological project whose goal is to find, document and digitize ancient graffiti from the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum,” she said. “We search for graffiti on the walls of these ancient cities, document them using archeological techniques and then digitize them in an online, free database so that anybody in the world can learn about ancient graffiti.”

Graffiti were probably ubiquitous in ancient cultures, DiBiasie-Sammons said, noting that ancient Rome, for example, was likely covered with graffiti, but the wall plaster preserving these engravings did not survive until modern times. Fortunately for the project – though unfortunately for the residents of Pompeii, Herculaneum and other nearby Roman settlements – the catastrophic eruption of Vesuvius buried Pompeii and Herculaneum, preserving the graffiti.

“Ancient graffiti give us a sense of what it was like to live 2,000 years ago,” DiBiasie-Sammons said. “One thing I’ve been struck by is that life 2,000 years ago was not so different than life today. We express some of the same sorts of thoughts and ideas and dislikes.

“I believe we can learn a lot about ourselves by looking to the past. This is one reason why the study of classics is important: by looking backward, we can learn a great deal about the present.”

During fieldwork in previous summers, the project, which started in 2014, has digitized more than 500 ancient graffiti, about 300 from Herculaneum and another 200 from Pompeii.

The project is directed by Rebecca Benefiel, an associate professor of classics at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia. The assistant director is Holly Sypniewski, an associate professor of classics at Millsaps College in Jackson.

Jacqueline DiBiasie-Sammons, UM assistant professor of classics, lines up a photograph of graffiti with reflectance transformation imaging, a type of computational photography. Submitted photo

The process for documenting the graffiti includes work both in the field and in the library, Sypniewski said. Project members study all published documentation of each graffito and, when possible, archival information.

That information is compiled into an electronic publication, but the project also studies those inscriptions that survive on site and records other information such as the graffito’s size, letter shapes and exact location. The project then photographs each inscription extensively and makes precise line drawings to record how each inscription appears.

“It’s a multistage and complex process that requires many different types of scholarly research and work,” she said.

This summer, DiBiasie-Sammons and three UM students, along with other members of the project, will return to Herculaneum to document the graffiti. Next summer, DiBiasie-Sammons will spend her field season in Pompeii, which once had about 8,000 graffiti markings.

Madeleine Louise McCracken, a freshman classics major from Austin, Texas, is one of those students going to Italy this summer for fieldwork.

“I hope to gain a firsthand knowledge of Roman culture and daily life in Herculaneum while also getting experience in the archaeological field,” she said. “It is a unique opportunity to put the knowledge that I have gained into context while also learning new skills that will help me in my future studies.

“I am fascinated with the lives and cultures of ancient civilizations, and I think that it is interesting and important to study their daily lives and compare how the ancients lived to modern society.”

The ancient graffiti were etched into wall plaster and differ from stone inscriptions, which were given forethought, while many of the graffiti were more spontaneous. But not all the engravings are impromptu words or phrases. There are poems, drawings of animals, prayers to gods for help – any number of inscriptions.

Since ancient Romans did not have cheap access to paper, items a modern human might write on a Post-it note, an average Roman citizen would write on a wall.

“Ancient graffiti are different than modern graffiti in that modern graffiti are either now illegal or frowned upon, but this doesn’t seem to have been the case in antiquity,” said DiBiasie-Sammons, who discovered her love of archeology during a second-grade field trip to an archeological excavation in her native Kentucky.

UM classics professor Jacqueline DiBiasie-Sammons takes a photo in Herculaneum, Italy, while working on The Ancient Graffiti Project. Submitted photo

“People were allowed to write in interior spaces of homes, but unlike today’s graffiti, which are typically large, spray-painted and draw your attention, ancient graffiti are usually really hard to find. They are often lightly scratched into the wall plaster, so if you’re not trained to look for this type of writing, it is easy to miss.”

The professors involved in The Ancient Graffiti Project seek out different types of funding to make the project possible: grants, support from project members’ home institutions and support from organizations such as the Center for Hellenic Studies, Sypniewski said.

Most recently, the project was aided by a crowd-funding campaign organized to help students participate.

DiBiasie-Sammons said UM has been “incredibly supportive, especially the Department of Classics. I have all the technological resources available to me that I need to do this research.”

The Mike and Mary McDonnell Endowment in Classics, created in 2009, also has been a wonderful resource for classics majors, particularly when it comes to travel overseas, DiBiasie-Sammons said.

“This summer, we will offer scholarships to any of the participating students who are classics majors from an UM Foundation fund generated from the Mike and Mary McDonnell Endowment in Classics,” said Molly Pasco-Pranger, associate professor and chair of the Department of Classics.

“The McDonnells’ first priority for the endowment is summer travel to classics students to study archaeological sites, so this project fits with their desires perfectly. We are hoping for an even bigger group of undergrads to participate next summer, when we offer a class in connection with the project.

“The study of ancient graffiti offers an incomparable window into the daily life of Romans of every social class that will allow our students to connect with the culture they are studying in new and vivid ways.”

The Ancient Graffiti Project also gives students a chance to do independent research, DiBiasie-Sammons said.

“This material hasn’t been studied extensively so there’s opportunity for students to do completely original research that makes a significant contribution to the field,” she said. “This is a wonderful opportunity for students to really make a difference in our understanding of the ancient Romans.”

Keep up with the faculty and students involved with The Ancient Graffiti Project during the field season this summer by following the project on social media via Herculaneum Graffiti Project on Facebook or @hercgraffproj on Twitter.