Classics, engineering professors team up to explore ancient history

NOVEMBER 26, 2018 BY

Brad Cook, UM associate professor of classics, balances an ancient Greek inscription over an X-ray fluorescent spectrometer as Lance Yarbrough, assistant professor of geology and geological engineering, and Melanie Munns Antonelli, collections manager for the University Museum, watch. Photo by Kevin Bain/Ole Miss Digital Imaging Services

It is a delicate balancing act Brad Cook performs as he places a more-than-2,000-year-old golden Greek artifact atop a high-energy X-ray fluorescence spectrometer. In position, the wafer-thin ancient article soon will be beamed with billions of photons, all to unlock its age.

Cook, an associate professor of classics at the University of Mississippi, is working in a back room of the University Museum on an October morning alongside Lance Yarbrough, UM assistant professor of geology and geological engineering, and Melanie Munns Antonelli, the museum’s collections manager.

Today meets a yesterday of centuries ago as the trio is using the spectrometer to peer into a gold, and then a bronze, inscription to discover the elemental compositions of the Greek relics. The results will offer a clue whether the inscriptions – both part of the museum’s David M. Robinson Memorial Collection of Greek and Roman Antiquities – are ancient or modern.

Because it is undetermined where the inscriptions were originally found and because the survival of metal inscriptions is so rare – they were commonly melted down, even in antiquity, and “recycled” – there is doubt as to whether the inscriptions are ancient or more modern. While the scans cannot prove the plaques are ancient beyond a doubt, they can reveal the absence of anything that would signal modern manufacturing.

After scanning, the gold inscription is found to contain 99.8 percent gold, with the remaining 0.2 percent being below the detection limit of the device. The bronze inscription’s makeup is 82.2 percent copper and 17.8 percent tin. The percentages are definitive.

“The results of the scans for the two metal inscriptions show that there is nothing modern about the composition of the metals,” Cook said. “These scans, then, provide an answer that is one of many answers that collectively build a case that argues for the antiquity of both inscriptions.

“Without these scans, there would always be a ‘what if?’ hanging around the room. In the broadest terms, every artifact has a story to tell, and these artifacts in the museum have, I suspect, a unique story to tell.”

The research into the composition of the inscriptions continues Cook’s work from earlier this year, when he received a $21,000 National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship to study the two inscriptions, including five months of work based at the American School of Classical Studies at Athens in Greece.

While other parts of the roughly 2,000-piece Robinson collection have been the subject of published works, these inscriptions – both about the size of an index card – have not been.

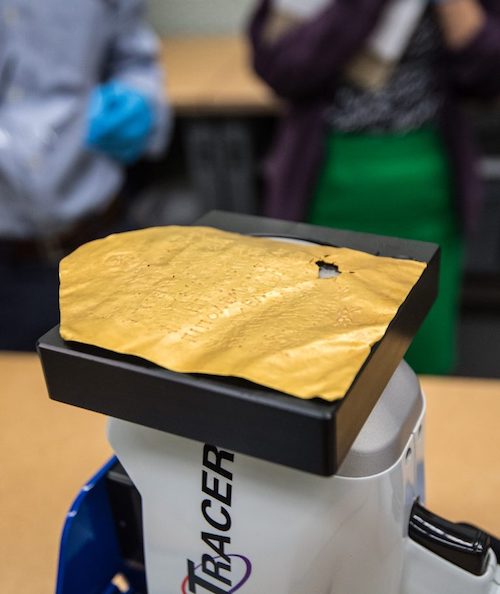

A gold Greek inscription, an artifact at the University Museum, records the essence of a defensive treaty between Philip V, king of Macedon from 221 to 179 B.C., and the city of Lysimachia. Photo by Kevin Bain/Ole Miss Digital Imaging Services

The gold inscription records the essence of a defensive treaty between Philip V, king of Macedon from 221 to 179 B.C., and the city of Lysimachia, a strategic town on the Dardanelles between the Aegean and Black seas. The bronze inscription records the freeing of a slave woman named Philista in northwestern Greece about the same time.

“A ‘mini’ version of a treaty on gold is, however, unparalleled, so much of my research is trying to finding comparanda for such things so I can answer … what is the purpose of a gold epitome of a treaty,” Cook said.

Classics and engineering might seem like strange research partners, but Cook has a friend, Scott Pike, an archaeological geologist at Willamette University in Oregon, who uses a spectrometer. Witnessing the usefulness of the instrument in that line of work and how it might aid him, Cook asked Pike where to find such an instrument. He told Cook: Ask your geology department.

“Brad sought us out,” Yarbrough said. “He emailed my chair, Dr. Gregg Davidson, hoping we had an XRF device. I only recently purchased the device in the spring of 2017, so it was good timing.

“One of the most useful aspects of (X-ray fluorescence) is that it is nondestructive. Many other methods of elemental analysis require you to destroy or consume a portion of the item.”

The spectrometer, a Bruker Tracer housed at the UM School of Engineering, is an apparatus that knocks electrons loose from their atomic orbital positions via an X-ray beam. The resulting burst of energy yields an elemental fingerprint that the instrument categorizes by element.

During the course of all this knocking, yielding and categorizing, the instrument ejects a minimal dose of radiation right above its “eye.” It is a “really safe” level, Yarbrough said. Still, he wears a radiation badge dosimeter just as a precaution.

His advice? Don’t stand over the spectrometer while it is beaming.

While handling the relics, Antonelli and Cook have their own safety precautions, wearing either white cotton gloves or blue industrial nitrile gloves when carefully positioning the articles over the “eye” of the spectrometer. Once the instrument starts lighting up yellow to red, everyone stands back and awaits the elemental composition percentages to calculate on Yarbrough’s laptop.

A scan takes a minute or two from positioning to final percentages.

Having answered the questions about the elemental composition of the two inscriptions, Antonelli, Cook and Yarbrough soon get curious about the composition of other museum artifacts, including ancient arrowheads, a jug and a ladle, which is found to be a surprising 67 percent silver.

The trio is having fun with its work, letting scientific inquisitiveness run wild for a while, but what they are uncovering is also valuable information to be used by future researchers.

“Understanding the composition of the artifacts helps us determine whether it may be modern or ancient since it is harder to visually date metal artifacts,” Antonelli said. “As the University of Mississippi Museum, we strive to be accessible for all scholarly research and to educate the public about our collection with the most accurate information possible. Any new information aids in this mission.

“So much of the antiquities collection could benefit from further scientific study. In the past, doing this kind of testing would have necessitated sending the artifact to another university. It’s wonderful that we have this technology on campus, and that Lance has been such a collegial partner readily willing to help Brad with his research.”