Mikaëla M. Adams, assistant professor of history, enjoys introducing students to Native American history and watching them evolve as thinkers, writers, and scholars.

Adams’ own introduction to the subject came when she was a sophomore at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. “I signed up for a Native American history class only to fulfill a requirement,” she said. From that first class, she was hooked. “I had a fabulous professor, Daniel Cobb, who helped me see American history in a whole new way.” Adams’ interest in the process of cultural contact, adaptation, and the legacies of colonialism led to master’s and doctoral degrees at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill.

She considers the study of Native American history a neglected part of the story of the U.S. “Often in textbooks, Native peoples just show up in the beginning of the story—they are there to meet Columbus, and engage in a few colonial wars, but then they seem to disappear. This is simply not true,” Adams said. “Native people were active and ongoing participants in the story of this nation and they continue to be today.”

Native American history enriches and complicates the understanding of race. “Indians didn’t fit into the black-and-white binary of the Jim Crow South, for example, so by studying their place within that society we learn about how and why those racial categories were constructed in the first place,” Adams said. “This story is critical not only for understanding the past, but also for understanding the present, as well as thinking about ways to break down racial barriers and discrimination in the future.”

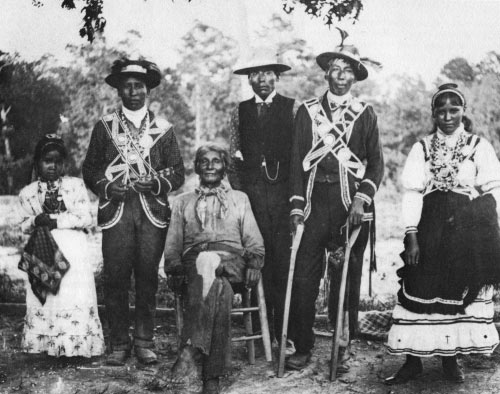

Adams’ first book, Who Belongs? Becoming Tribal Members in the South, looks at how Southern tribes constructed their identity and worked within the context of the Jim Crow South to create ideas of who belonged to their communities based on cultural traditions and kinship practices, but also on the realities of living in a segregated, black-and-white world.

In her examination of how tribes repurposed older notions of kinship and culture to create new criteria of belonging to meet the challenges of living in a world defined by racial classifications, Adams focuses on the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians of North Carolina, the Pamunkey of Virginia, the Catawba of South Carolina, the Seminole and Miccosukee of Florida, and the Mississippi Band of Choctaw.

The medical history of Southeastern Indians’ response to the 1918 influenza pandemic and its affect on traditional healing practices is Adams next project.

“I joke with my students on the first day of class that you never know what will happen when you sign up for a class just to fulfill a requirement!” she said.