By LUCY SCHULTZE | Courtesy of The Oxford Eagle

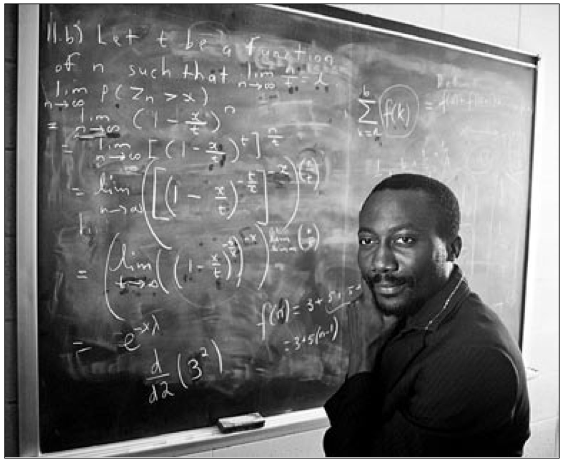

Martial Longla, assistant professor of mathematics at the University of Mississippi | Photo by Bruce Newman, Courtesy of The Oxford Eagle

Raised in a poor village in west Cameroon, Martial Longla could have succumbed to the hardships fate dealt him. Instead, he gave in to the appeal of a daunting challenge.

Cryptic equations scribbled on a chalkboard looked like a mountain begging to be climbed, as Longla sat in his high-school classroom, captivated. Today he’s scaled those heights to secure his first academic appointment, as an assistant professor in the University of Mississippi Department of Mathematics.

Longla officially joined the faculty this semester, coming from the University of Cincinnati, where he earned a doctorate as well as a second master’s degree in statistics. This semester he’s teaching a total of about 70 students, in foundations of mathematics and in calculus.

Previously, Longla spent a decade in Moscow as the result of a scholarship opportunity. He learned the Russian language and also honed his English skills, earning money for necessities by working as a three-way translator with his native French.

His time in Russia was a rich experience of social activism and creative expression, as he employed African dance, singing, percussion, poetry and humor in an endeavor to correct the prejudice that people of color faced in Russian society.

While he misses the stage, he’s focused for now on getting settled in his new environment in small-town Mississippi. He chose UM over job offers in New York, both for the warmer climate and for the connection he felt with colleagues in the math department here.

His wife has remained in Cincinnati thus far, but he hopes she’ll be able to join him soon.

The Oxford EAGLE visited with Longla, 35, in his office in Hume Hall.

So how are you liking Oxford so far?

“I think it’s going to be fine. I’m not yet seeing what people were telling me that I’m going to see here.

“I was at the airport, and there was a lady there—apparently from Ohio, where I came from. And I was in my African dress, so she was interested and she said, ‘Where are you coming from?’ ‘I’m coming from Cincinnati.’ She said, ‘And where are you headed?’ I said, ‘Oxford.’

“‘Oxford, Ohio?’ ‘No, Oxford, Mississippi.’ What did you forget there?!’ ‘What do you mean?’ She said, ‘You are going to see.’

“That was two months ago. So I’ve been asking some of the colleagues around: ‘What is it that I’m not yet seeing?’

“You know, some people are still living in the past. Even when I told my friends that I had some job offers, and then I decided to go to Mississippi: ‘Martial, what is wrong with you?’ They said, ‘You do know the history, right? And you are going there?’ ‘Yes, I’m going to Mississippi.’”

Was mathematics something you connected with early on?

“No. To be honest, when I was in primary school, I was very good at languages. So everybody was sure that I was going to be a journalist, and that is what I was aiming for. All the time you would see me reading. I was not doing the exercises in mathematics. I was not interested at all. I was just an average student in a class—until I got to high school.

“About half way in high school, I met an instructor. If I did not meet that man, I don’t think I would be doing mathematics. The instructor comes into class—just a young boy, like me. He was just as short as I was at that time. And then he doesn’t have any notes. He comes just with a piece of chalk. And then he asks a question: ‘Where did we stop last time?’ You tell him. He goes to the board and continues the lecture.

“‘Example.’ It comes from the brain. ‘Solution.’ He gives you the exercises, and he doesn’t look anywhere. Come on! A human being can do this, and I cannot understand it? This is not normal; it cannot happen this way. And then I told my friends: ‘I’ll become a mathematician.’”

How did your work change from that point?

“I started studying. Every day, I get back home, first thing before I eat, I go to the board, review all the theorems we had in class, try to prove them without opening the notes, make sure I understand what was there, then do the exercises before I eat. Every day, every day. My parents said, ‘What is happening with this kid?’ My mom said, ‘Martial, what do you do? You used to like to eat, now you don’t eat at all.’ I said, ‘It’s OK. I just know what I want.

“From that point on, things started to change. The next test, I get a 16 out of 20. Then a 17.By the end of the year, every test that comes, I have 20 out of 20.Then I become the first-ranked student in the class.”

Why did you pursue your studies in Russia?

“I didn’t have other options. Scholarships are very hard to obtain, and it was a surprise for everybody when I actually got it. My father was like, ‘How did you do that?’ I’m like, ‘I don’t know. It just happened.’ Because usually, when scholarships come, by the time you hear there are already some applications from other people—from the circle of people who know about that, so they just go ahead and have their relatives apply.

Back in my village, it was very far from the capitol city where you have the Ministry of Higher Education, where all those scholarships are.

“When I moved to the capitol city for the university, a friend said to me one night, ‘Martial, I heard you were interested in traveling abroad. Do you know I was passing by the Ministry of Higher Education, and I saw them putting an advertisement that there were some scholarships for Russia? The deadline is tomorrow.’ We are at 5 p.m. I said, ‘Really?’ She said, ‘Yes, if you’re interested.’”

How did you make that deadline?

“I called all my friends. I said, ‘Guys, this is the thing: I shouldn’t miss this. Here’s what they want. You go for this document, you go for this document, and we all meet at the ministry at this time. One person will go to notarize a birth certificate, the other will go to collect the pictures, the other a certificate that I’m healthy. And everybody just rushed. They all gave me everything they had, and I knocked at the door.

“The people looked at me. I said, ‘I’m coming for the scholarships to Russia.’ Someone said, ‘Oh, really?’ ‘Yes.’ So a lady takes the papers. She ‘How? What? You got a 19 out of 20 in mathematics?’ ‘Yes.’ She’s like, ‘OK.’ She looks at physics, 19.5. Chemistry, 18. Then she looked at me and asked: ‘Do you really want to go to Russia?’ I just asked her as an answer: ‘Do you have other options for me?’ She looked at me again and said, ‘OK. Just come back when the results are out. We will need your HIV test at that point.’”

So where did you end up?

“I ended up in a southern town of Russia called Rostov-on-Don. I had no money and couldn’t get anything from my parents. So, my only hope was success. After several months in a hospital with a broken knee junction, I decided to transfer to Moscow.

“I was in Moscow, at the People’s Friendship University, with a very large family of foreign students. With the student organizations fighting for the students’ rights and things like that—trying to prove that the black guys are not as bad as they think they are. So we had to go to some Russian high schools, talk with the kids about African culture, show them some plays and performances. This was backed by the Peoples’s Friendship University of Russia, that in his mission wanted to work for more integration in this world. ”

It sounds like sort of a cultural-ambassador role.

“That’s mainly what we were doing, yes. It was very exciting, and when people started talking about what it would be like here, I said, ‘Hey, I don’t think there is anything that you can go over that I haven’t seen in my life.’

“I’ve been called names. I’ve been called names by my own students—before realizing that they’re going to be my students. They call me ‘monkey,’ and then the next day, they would come in the classroom and I would be in front of them. In Russia, you’d have some groups of young guys going around beating guys. These guys were supported and paid by some extremists that needed to prove that the government was not protecting foreigners in Russia. I know this because some TV programs I was invited to featured some of the mentors of these young folks. So, one pays another to harm You, while others try to protect You in the same country! So I don’t think there’s anything that might happen to me here that I haven’t seen.”

Do you feel a gap between your experience and that of the students you teach here?

“When I look at the students in this country which were in the same conditions that I was in, I don’t see them behaving the way I was behaving. Because, I think, of politics. And the second thing is because of the system itself.

“Because when you put too much accent on the fact that we don’t have opportunities, we don’t have options, we don’t have this, we don’t have that—you end up having people that don’t try to do their best. Not that they are unable to do so, but because they just know that’s how it is.

“So most of the time, when I talk to the students, I just try to make them understand that being a minority is not a reason to fail. Is not a reason to expect that people will be just giving away grades to you, to make sure you go through. Because doing that doesn’t help you. It keeps you where you were.

“So if you need to succeed, get that out of your brain. It’s true, yes. It’s true that you are from a minority and that there has been some discrimination, and that maybe still exists. But for you to succeed, you need to make sure you put in that brain: It’s all up to you. You’re not living in history. You’re living right now. And right now is the time for you to do the right thing.”

Why choosing the U.S. over Russia?

It was not a choice. It was a necessity. I loved my environment in Russia. I never thought I will ever move away from Moscow. The Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia was like a country inside Moscow, with its own government and rules. The rector of the University was a very good man and was very supportive of my actions. He personally wrote a letter of recommendation for me when I told him that I needed to move to US. I was worried about my future. I needed to secure a place where I could live with my wife and possibly my parents. I understood that for my 22 brothers and sisters, and my own family, I needed to do more. My heart still beats for Moscow. I will not say that I regret coming to U.S. but I am certainly not happy for moving from my main land—RUDN.