Renowned immunologist Dr. Max Cooper wins Japan Prize

DECEMBER 27, 2018 BY

UM alumnus Dr. Max D. Cooper, of Emory University School of Medicine, is a laureate of the 2018 Japan Prize, one of the most prestigious scientific awards in the world. Photo by Jack Kearse

Dr. Max D. Cooper, of the Emory University School of Medicine, didn’t become a researcher to win awards. As a pediatrician, his concern for his patients led him to explore why inherited disorders disable the immune system, leaving children vulnerable to infection.

Yet, numerous awards have recognized his pioneering discoveries, and the Mississippi native is a laureate of the 2018 Japan Prize – one of the most prestigious scientific awards in the world – along with the famed Jacques Miller of Australia, for the discovery of the dual nature of adaptive immunity, which identified the cellular building blocks of the immune system as we understand the system today.

Cooper, who earned his medical certificate from the University of Mississippi in 1955, and Miller were honored in April 2018 at a Tokyo awards ceremony after a highly competitive process. The Japan Prize Foundation jury considered some 13,000 nominations of prominent scientists and researchers from around the world.

The acclaimed awards applaud contributions to “the advancement of science and technology that promote peace and prosperity for all mankind.” Cooper and Miller won in the category of “Medical Science and Medicinal Science”; the other Japan Prize award, in the category of “Resources, Energy, Environment and Social Infrastructure,” went to Akira Yoshino, inventor of the lithium-ion battery.

“(Dr. Cooper’s) accomplishments have forever altered the face of medicine, and he is continuing to contribute to advancements that will improve the health of individuals for decades to come,” said Dr. Vikas P. Sukhatme, dean of the Emory University School of Medicine.

In 2010, the Koch Foundation in Berlin selected Cooper for the Robert Koch Prize – considered one of the steppingstones, along with other awards, to the eventual Nobel Prize.

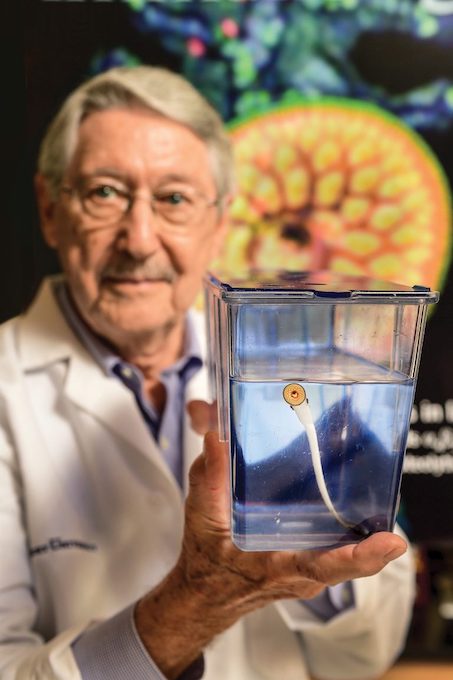

Max Cooper displays a juvenile lamprey. He studies lampreys for their dual immune system, similar to that of humans. Photo by Jack Kearse

“Max Cooper is one of the groundbreaking scientists of our time, and he is extremely deserving of this international award,” said Rafi Ahmed, director of the Emory Vaccine Center, referring to the Koch Prize. “His visionary fundamental discoveries laid the groundwork for many of the most significant advances in infectious diseases and vaccines.”

Cooper is a professor of pathology and laboratory medicine and a Georgia Research Alliance Eminent Scholar in developmental immunology. He also is a member of the Emory Vaccine Center, the Emory Center for AIDS Research and the Winship Cancer Institute.

Cooper’s research deciphers the two types of lymphocyte lineages involved in adaptive immunity, laying the conceptual groundwork for our understanding of nearly all fields touched by immunology.

His discoveries have formed the underpinnings of medical advances ranging from bone marrow stem cell transplants to monoclonal antibodies and, in recent years, the development of new immunotherapy drugs to treat cancer and antibodies for the treatment of autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease.

Paul Kincade, of the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation – Cooper’s first graduate student, a fellow Mississippian and world-renowned immunologist – shared the impact of his mentor’s research in layman’s language.

“It is easy to understand Max’s most important contributions,” Kincade said. “He showed that the immune system is composed of multiple types of cells that have discrete origins and functions. One major type is responsible for making antibodies, while another kills virus-infected cells and tumors.

“This basic understanding changed everything, making it possible to better understand immunodeficiency, autoimmune diseases and cancer. Max has expanded and refined these concepts, suggesting new research questions for others to pursue.”

If Cooper’s upbringing can be linked to his stellar career – and he says his parents had “everything to do with it” – the influential scientist makes a strong case for young people being encouraged to use their imaginations for entertainment.

“My childhood was rich in unfettered time, space to roam freely, woods and streams to explore, an uncontaminated view of starry night skies to ponder and an abundance of books to read,” Cooper said. “The treasure of books and the thirst to read them were gifts of my father, a mathematician and educator who loved learning, and my mother, who was also a dedicated teacher.”

He was born in Hazlehurst and grew up in Bentonia, just north of Jackson. His home and the school where his father worked as superintendent were filled with books, sparking Cooper’s interest in the rest of the world.

“Little did I imagine while growing up in rural Mississippi that I would eventually pursue a research career in immunology,” the physician-scientist said. “One of the most remarkable things about a career in biomedical research is that one can start almost anywhere and end up in the most unforeseen places, being constantly amazed by what you are learning along the way.”

Tragically, Cooper lost his “wonderful and adventurous” older brother in a car accident, when Cooper was a high school senior. At that time, his grieving father took him aside to tell him that he must carry on with the plan for both brothers: in his case to become a physician.

Cooper’s college career began at Holmes Community College in Goodman, and with its football team, but he quickly surmised that he was a slow quarterback who was definitely not going to see fame or fortune on the gridiron. He transferred to UM, where after his studies he enjoyed such quintessential college life activities as attending football games, going to dances in the Student Union and playing cards with friends.

Cooper earned his medical degree and completed his residency in pediatrics at Tulane University before more training at the Hospital for Sick Children in London, completing a fellowship in allergy and immunology at the University of California in San Francisco and making a second stop at Tulane University. He persuaded the famous Dr. Robert Good – a founder of modern immunology and a pioneer in bone marrow transplantation – to invite him to join his research program at the University of Minnesota Medical School.

Arriving with only limited laboratory skills and an audacious desire to enter a highly competitive research field, Cooper was assigned about 3 feet of bench space and a drawer in the crowded laboratory. Fortunately, Cooper’s determination enabled him to persevere.

“When difficulties arose over the years, I often recalled the pep talk of my early mentor, Bob Good: ‘What we know compared with what we don’t know is like a crumb in the corner of this room. As long as you start with a reasonable hypothesis and do the experiment right, you’re bound to find something new.’

“This is likely still true, and I cannot imagine a field of research that is more exciting or one that offers a better opportunity to explore the balance of life on our planet. Perhaps this view explains why I am hooked for life with immunobiology.”

After four productive years in Minneapolis, Cooper embraced a 40-year career at the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine, during which time he was inducted into the Ole Miss Alumni Hall of Fame in 1992. He directed UAB’s Division of Developmental and Clinical Immunology for more than two decades, after leading the Cellular Immunobiology Unit at the UAB Comprehensive Cancer Center for 12 years. He joined Emory University in 2008.

Cooper chuckled when he explained that many of his graduate students have already retired, while his fascination with discoveries and his natural curiosity keep him involved in research activities, speaking engagements and international travel. And Kincade, that inaugural student, said he remains a scholar of Dr. Cooper’s some 50 years later.

“Countless scientists consider themselves his pupil, and there are several reasons for this,” Kincade said. “Firstly, he is the son of educators and cares deeply about the transfer of knowledge.

“Max is the best communicator I have ever met and continues to be in great demand as a keynote speaker. He manages somehow to excite audiences with his important discoveries without bragging. It would be wonderful to know how many listeners and readers of his publications have changed direction under his influence.”

The unique gift Cooper possesses?

Photo courtesy of Max Cooper

“Max Cooper is the best coach any scientist could ask for, believing and encouraging when things seem to lack promise,” Kincade said.

In this regard, the researcher and physician also has his parents’ gift for teaching. He has advised and trained 30 doctoral students and 115 postdoctoral researchers in his laboratory.

In recent years, Cooper, joined by his wife, Rosalie Lazzara Cooper, made a major contribution to Ole Miss that both celebrates his relationship with his alma mater and honors his parents through establishment of the Otis Noah and Lily Carpenter Cooper Education Fund. The scholarship endowment was created “to honor these educators’ lifelong devotion to the learning process, to recognize the vital contributions that all educators make to society and to provide income for scholarship assistance to deserving students at the University of Mississippi.”

Those eligible for the scholarships are sons and daughters of educators. Ten Ole Miss students have already benefited from the financial academic awards.

Cooper is a member of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, the Academy of Medicine and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He is a former president of the American Association of Immunologists, the Clinical Immunology Society and the Kunkel Society.

In 2017, Cooper received the Emory 1% Award, which is reserved for faculty whose National Institutes of Health proposals have been ranked in the top 1 percent by NIH reviewers. In addition, he was bestowed the Legion of Honor Medal by the president of the French Republic and was elected to the Académie des Sciences, Institut de France and to the Royal Society of London.

Before the Japan Prize and the Robert Koch Prize, his honors include the Founder’s Award of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine (1966), Sandoz Prize in Immunology (1990), American College of Physicians Science Award (1994), AAI Lifetime Achievement Award (2000), AAI-Dana Foundation Award in Human Immunology Research (2006) and the Avery-Landsteiner Prize (2008).

Emory University News contributed to this article.

This story was reprinted with permission from the Ole Miss Alumni Review. The Alumni Review is published quarterly for members of the Ole Miss Alumni Association. Join or renew your membership with the Alumni Association today, and don’t miss a single issue.